In the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, energy poverty has long been a central issue in the everyday lives of the shrinking population. EnergyMeasure’s partner Tighean Innse Gall provides concrete measures for people’s everyday lives.

Whaling was practiced on the Outer Hebrides in northwestern Scotland until the 1920s. The animals’ fat, meat and bones were once important raw materials. And the oil extracted from the large bodies was an energy supplier. In the 1950s, the old Bunavoneader whaling station on the Isle of Harris was put into operation once again for a short time before whaling ended in the British Isles. A brick chimney is still visible for miles around as a remnant of the whaling station.

Today, Joan lives above the whaling station. The spry pensioner is 85 years old. She lives in her own house, which her father, who was a gamekeeper talented at making fishing lures, was able to buy here decades ago. The property also houses a small cottage that is rented to tourists and offers a great view over the bay, and a large vegetable garden for self-sufficiency.

An energy plan for every household

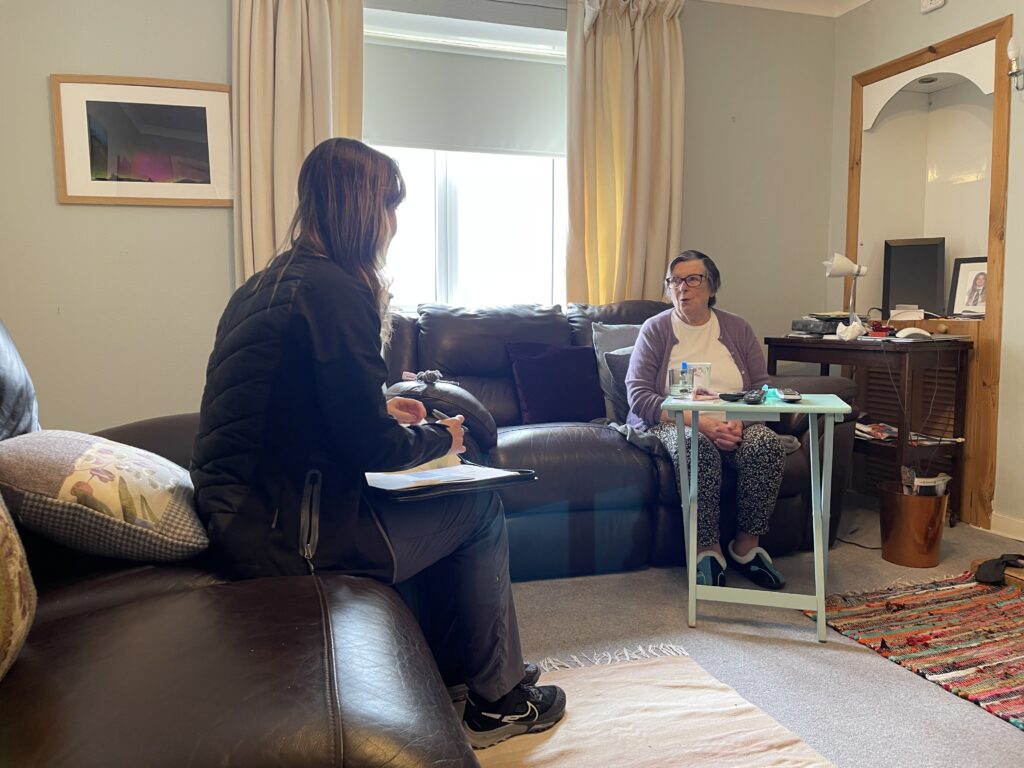

Joan‘s is one of the households that Charley Healey advises on energy efficiency as an energy advisor for Tighean Innse Gall as part of the EnergyMeasurs project. When Joan signed up to the project Joan was paying over 60% of her low income on heating and electric. On her last visit, Joan worked with Charlie to convert her bedroom lighting to energy-saving bulbs. And before that, Joan has already implemented several measures according to a fixed set of measures that Tighean Innse Gall offers to participating households. These include, for example, an air fryer, which has a big impact on energy consumption for cooking in single-person households like Joan’s. “Every household gets an energy plan and that lists all of the things that we’ve discussed during the home visits. It gives you the monetary savings of the measures installed and also potential savings from behavioural change. It’s to empower households.” Charley Healey explains.

Joan has changed her energy-related behavior also in the way she uses the rooms of her house. “I had the insulation done and I noticed that the thermostat went from danger of hypothermia to one notch up. It made a bit of difference, but not a huge difference. That was because there was no heating upstairs, simply, because I could not turn on the convectors. It was too expensive. I don’t think anybody would be able to turn them on. So the upstairs was quite cool.” So finally, she decided to sleep in the ground floor, which she now heats sufficiently.

Energy poverty doesn’t equal poverty

The harsh climate, rising energy costs, settlement patterns, demography, and the traditional ways, houses are constructed in the Outer Hebrides have led to a particularly high risk of energy poverty for the approximately 20,000 inhabitants of the scenically spectacular archipelago. Many of the households affected are not poor in the classic sense of the word. That’s because energy poverty is not the same as poverty, Brian Whitington explains: „If you’re a pensioner on a state pension in the United Kingdom, your income is about 8000 EUR a year. If you’re a pensioner who also requires the use of dialysis machine at home, using that machine would cost you 2000 EUR at current unit cost price. If you can’t afford your energy bill, you can’t use your dialysis machine. If you’re a mother with a young child, and your housing is payed through housing benefit, as it is in the UK, you may get food from a food bank, but if your energy bill is so high that you can’t pay it, then how would you cook that food? There are many circumstances where you may be uniformly poor. But energy poverty has direct consequences that differ in that you can’t cook food, you can’t store food, you can’t keep warm, you can’t turn the lights on. If you have children and you can’t turn the lights on: How would they do their school homework?”

In the Outer Hebrides, 50 per cent of the population are affected by energy poverty, Whitington says. “There is a direct correlation between energy poverty and attainment levels in education. What does that mean for life chances?” For the Outer Hebrides, energy affordability has long become a matter of existence. The potential for harnessing wind power appears enormous. Currently, however, the infrastructure is still lacking to use larger amounts of energy from renewable sources not only locally, but also to transport it to the British mainland. Community-owned wind turbines offer hope for a more favorable local energy supply. Like the end of whaling in the Scottish islands, the energy transition is a game changer for residents. Providing not only clean energy, but also affordable energy, is critical.