The behaviour change approach

Human behaviours are not simple or straightforward, they are complex, non–linear and influenced by a number of various factors (Lucas et al., 2008). People’s behaviours determine how they act socially within particular environments, and tend to be influenced by emotions, habits and morals, as well as social and normative factors. These many influencing factors can make changing behaviours challenging (Martiskainen,

2007).

Energy-related behavioural change

There is widespread recognition of the potential of energy–related behaviour change to address rising energy use and its climate effects (Heimlich and Ardoin, 2008; Moloney, Horne and Fien, 2010). However, there are many (individual, social, and structural) barriers which limit an individual’s willingness (and indeed their ability) to alter their personal behaviour and lifestyles, despite a high level of general public support for addressing climate change (Ockwell, Whitmarsh and O’Neill, 2009; Hayles and Dean, 2015).The development of effective intervention strategies for targeting energy behavioural change is dependent on our understanding of energy conservation behaviours.

Recent research has led to energy conservation behaviour been categorised into two distinct dimensions:

efficiency and curtailment behaviours.

Efficiency behaviours

These are once-off behaviours that may necessitate occasional actions, e.g., purchase of efficient appliances or equipment or investment in structural changes. While there is a financial outlay associated with these behaviours, they do not result in lost amenities and generally produce longer-lasting effects (Karlin et al., 2014). Efficiency behaviours can be further divided into high-cost (e.g., installation of insulation) and low-cost measures (e.g., replacing incandescent lamps with LED lights)

Maintenance behaviours

Sweeney et al., (2013) also identifies the maintenance and repair of energy-using appliances to improve their performance and efficiency.

Curtailment behaviours

Referring to no-cost (or very low-cost) energy-saving behaviours requiring repetitive efforts to produce energy savings, including e.g., turning off light switches, lowering thermostat settings, closing curtains, etc. Karlin et al., (2014) reports that some associate them with reduced amenities or decreased comfort. The energy-saving potential of curtailment behaviours is generally considered less than that of efficiency behaviours (Gardner and Stern, 2002)

Behaviour Change Interventions

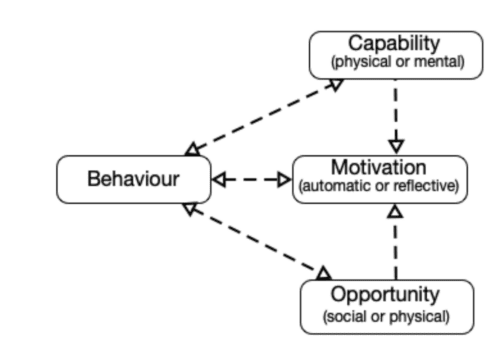

Behaviour change interventions can be understood as those actions designed to influence a specific behavioural pattern, at both the individual and societal levels. Michie, van Stralen and West’s (2011) Behaviour Change Wheel offers a framework for understanding and designing behaviour change interventions. The core of the BCW framework is the COM–B model, which posits that there are three interlinking sources of human behaviour (which in turn are influenced by behaviour)

Other articles

“I feel a bit frustrated when I feel like people aren’t tackling energy poverty because they’re waiting for it to be defined.”

Marilyn Smith is a Paris based journalist with a background in energy reporting. She is responsible for the communication of the Energy Action Project. We talked to her about how diverse the manifestations of energy poverty are in Europe, and why it is not always easy to generate attention for this issue.

Tips & tricks for saving energy and reducing your energy consumption bills

Energy efficiency means using less amount of energy, reducing your home’s energy waste and saving money. To effectively increase energy efficiency involves diverse but simple approaches. But in particular, energy saving measures require the process of creating awareness.

A Chain-Reaction of Negative Consequences of Living in Energy Poverty

A series of interviews conducted with citizens and stakeholder organisations shows how people experience energy poverty and also the institutional support offered to affected households in seven European countries.